S1 E4: Mary Hooks & Kate Shapiro on ending bail in ATL & the Black Mama’s Bail Outs

December 6, 2022

Episode Guests

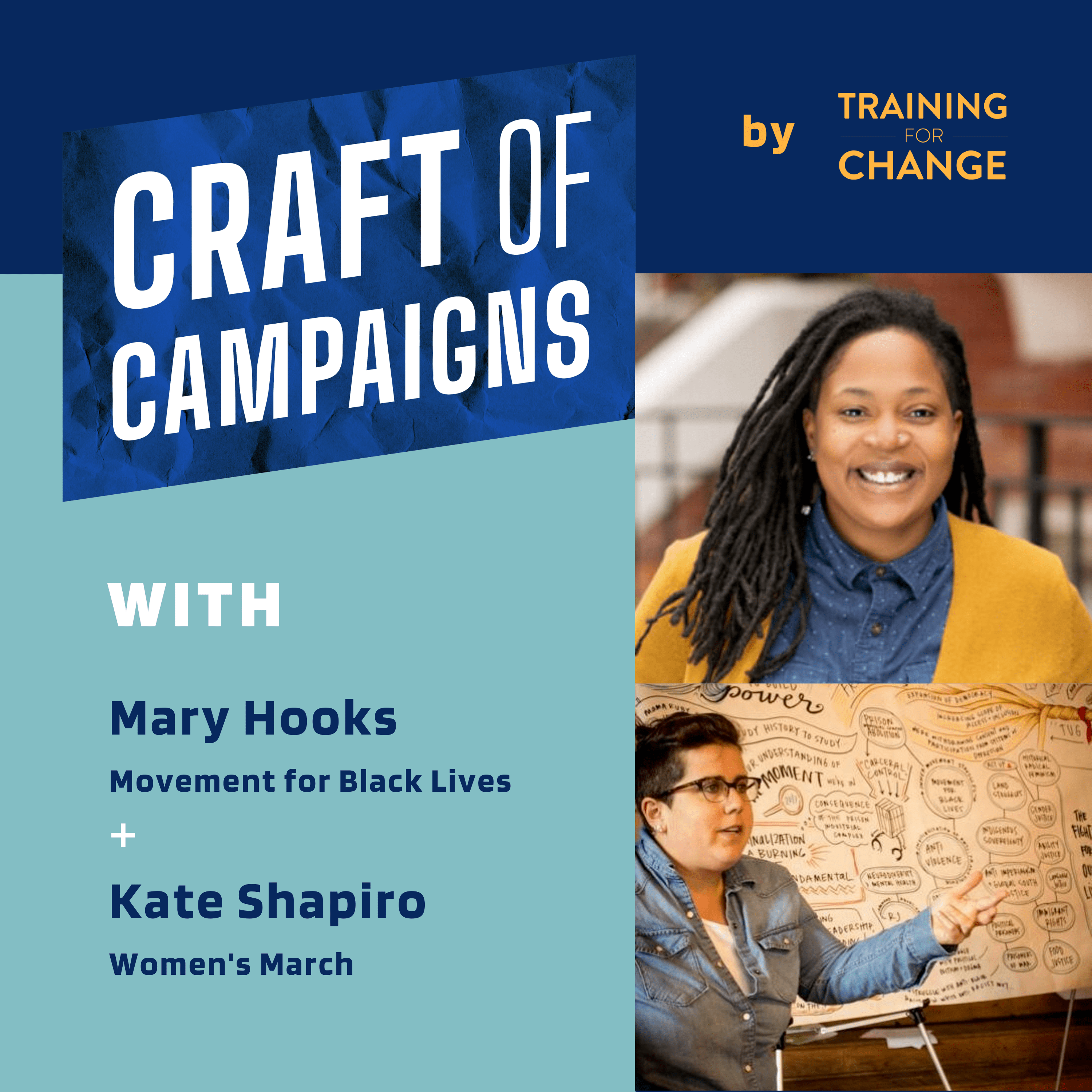

Mary Hooks is a Black, lesbian, feminist, mother and Field Secretary on the field team for the Movement for Black Lives. Mary is the former co-director of Southerners on New Ground (SONG). Mary joined SONG as a member in 2009 and began organizing with the organization in 2010. Growing up in a family that migrated from Mississippi to the Midwest, Mary’s commitment to liberation is rooted in her experiences and the impacts of the War on Drugs on her community.

Kate Shapiro was born in Durham, North Carolina, and raised in Atlanta, Georgia where she still lives with her daughter. She has had the great honor to work in the service of US Southern freedom movements for gender, sexual, racial and economic justice for the last 16+ years. She is a grassroots organizer, trainer, popular educator and strategist. She has worked at Women’s March since 2020 and was on staff at SONG in a variety of roles for 8 years before that.

SONG’s Free From Fear Campaign: The Birth of Black Mama’s Bail Outs

By Andrew Willis Garcés | abridged version published in The Forge

Download as a PDF

This story starts in 2010, when SONG’s leadership set course for a five-year plan that would emphasize broadening and expanding their base in regions outside Durham, NC and Atlanta, GA According to Mary Hooks, who came on staff as an organizer in 2011 and would later become the group’s co-director, the question was, “how can we leverage the infrastructure of the regional organization in order to get some concrete wins and material changes for our people while also embodying and demonstrating what intersectional organizing looks like? Not just the identity politics stuff.”

To do that, SONG had been engaged in issue identification work, surveying members and queer people throughout the South, and consulting the organization’s elders and strategic advisors. Those organizers pointed them towards the fight to defend public education.

Kate Shapiro, a SONG organizer at the time, says “it was a moment where, we were junior organizers tasked with an intergenerational process with older organizers to build this out and they said, ‘public education.’ And we were like, ‘okay’. And then we told everybody to explore that issue through surveys and different types of research.” But it didn’t resonate enough with the group’s base. “It was politically a sound strategic decision that, you know, that’s when the charter school stuff was still in its infancy,” said Mary. “We saw it coming and so we thought that there was some ways in. But many of us were out of school and didn’t have school age children. And so it wasn’t felt deeply.”

But the surveys throughout 2012 and 2013 led them towards criminalization. “They would say, ‘but I will tell you I’m struggling in public [space].’ Whether that was a little homey, Chuy Garcia, right outta Durham who was killed at a skateboard park, and it had really energized and charged up a lot of people there… we went to Charleston, even the queer clubs were overly policed,” said Mary. “We started with the banner of ‘beloved community’ and that was going to be our work around public education. And then we decided to focus more around criminalization under the banner of freedom from fear.”

“That’s also the point at which we started talking about quality of life versus life and death issues. A lot of the more mainstream, more elite [LGBTQ] organizations be them gay or not were often pushing around quality of life improvements and where we were casting our lot was around life and death issues.”

The group’s initial 2014 test campaign would be in Durham. They decided to launch into creating a comprehensive bill, eventually called the Durham Community Safety Act, which SONG referred to internally as “the omnibus bill”. “Showing our ignorance a little, she laughed, “we created this ordinance which had 49 demands in it, at least, we had everything from standard operating procedures in there to consent searches… we packed it all in,” said Kate. “People would tell us, ‘yo, you doing the most [with this bill]” confirmed Mary. At the time of the campaign’s January 2015 launch, the demand was for passing a comprehensive anti-discrimination ordinance. But after getting feedback from local advocates and elected officials, it was narrowed down, and in 2016 — in the wake of popular opposition to an anti-transgender law passed by the state legislature, HB2 — a local coalition that included SONG members won implementation of new standard operating procedures by Durham police for engaging with transgender and nonbinary people.

Both organizers described the Durham campaign as helping shape their approach to subsequent local campaign development: “We learned the hard way with that ordinance that we need to do our research on targets and decision makers,” said Kate. “What’s on paper is different than actually how power is brokered inside of our different municipalities in county decision-making bodies. But there’s always a tendency to get real deep in the weeds on the research forever and not actually test.”

This ability and eagerness to listen for possible campaign issues and quickly test them helped the group to move past a perennial source of ambivalence about where to launch the next campaign: whether to focus the organization’s resources on organizing within Atlanta, where the group had its regional office and a relatively significant membership. “We had never initiated our own work in Atlanta, it had always been as part of coalition. We wanted to make sure that we were driving resources to other parts of the region,” explained Mary.

Being part of the response to Michael Brown’s murder in Ferguson, MO, helped them decide. “Having rolled out to Ferguson during that October weekend, we was given a mandate from the Ferguson comrades to say, ‘it’s going down where you live, you know, it’s horrible where you live. So let’s go turn up all over.’ And so we came back, had like an affinity group of organizations that were doing all kind of actions.”

After another internal listening and issue ID survey process, SONG Atlanta decided to focus on the issue of unjust fines and fees assessed to (overwhelmingly Black) defendants in Metro Atlanta’s courts. To learn more about the issue the group participated in court watching, connecting with defendants in Failure to Appear courtrooms (for defendants who had missed a scheduled court appearance) and more formal study and political education, reading books like The Condemnation of Little B as a group to understand the history of criminalization. As they got deeper into relationship with people they encountered, their demands and understanding of their targets evolved.

Mary explains: “Initially our demand was ‘no fines and fees,’ and we wanted folks to be able to volunteer to do meaningful community service, because we had talked to folks that had been forced to wash cop cars as their community service. And then we added a demand to end the automatic bench warrants that get issued when folks fail to appear at court. I think that we added the bench card demand because we saw all the crazy shit in court watch where they’d be like, ‘oh, you got a cell phone. You can pay this $700.'”

“We were also getting punted back and forth between City Council, the local city judges and the mayor. They would each say, ‘no, no, no, we don’t make the decision. The judges made the decision.’ ‘No, we don’t make the decision. The mayor makes the decision.’ Literally everybody was telling us opposite things. They were just trying to play us.

“And so we’re like, ‘yo, let’s go ask the target.’ And so while we’re doing all this other stuff, still researching, court watching, we reach out to Chief Judge Chris Ward, and we say, ‘yo, we wanna meet him.’ And we reach out again and again, and homey don’t respond. And so we escalate our tactics and we had called all the other judges, and he had told them not to talk to us. And so we’re like, ‘okay, now we gotta show you what these scrappy queers is willing to do.'”

They decided, rather than continue to research and speculate on who moved the pillars of power, why not test our power map through direct action? “It will give us more data versus shuttling back and forth between all of these different offices,” as Mary described their thinking. Playing off the theme that Judge Ward had “failed to appear” for their communities by refusing to meet with them, SONG Atlanta teamed up with a local artist to design a fourteen-foot-tall “failure to appear” summons, which they held outside the court during the daily line-up to reach the metal detector, and simultaneously sent another team inside his courtroom.

“We had little ‘Judge Ward failed to appear’ signs, we had rolled them up and of course we put glitter in them. We intentionally sat at the front of his courtroom, and when they said ‘All rise,’ we all stood up like everybody else, but we opened up our posters, glitter falls out, glitter bombing, essentially. And then he’s like, ‘What is this? This is a courtroom, not a street corner.’ And kind of does like this chastising thing. And we’re like ‘answer the fucking phone’, and we walk out.” But that wasn’t the end. “He sends the bailiff after us, who says ‘the judge wants to meet with you in his chambers.'” They had finally won their meeting, where the judge refused to consider their proposals for more dignified community service and ending the use of bench warrants. “And that’s all we wanted , for him to be able to look us in the eye and tell us that he wouldn’t go meet our demands. ‘Great, enough said, sir.’ So now we know we can escalate in good conscience,” said Mary.

Over the course of 2015 and 2016 the group expanded its court watch program, and engaged more people with community town halls, gearing up for what they thought was a public fight centered on fines and fees. But then, they realized, what if there was a demand that would get closer to the root cause of the problem?

“We were going to the Failure to Appear courtrooms, but we had slipped into or accidentally went into the First Appearance courtroom, and we hadn’t before. And once we sat in there, I remember thinking, ‘this is a different entry point, cuz if we can address folks staying in jail, cuz they can’t afford their bail, they’ll be less likely to cop out or take a plea deal or just pay to fine. If we intervene here, we don’t even have to perhaps even deal with the fines and fees.'” Having defendants sit in jail because they can’t afford bail is a way prosecutors can put pressure on plaintiffs to plead guilty, incurring fines and fees. But if they were out of jail, Mary thought, they would be less likely to plead guilty in the first place.

She was further influenced by a report published around the same time about how the Ferguson police department had used bail as a weapon against the local population. Researching the issue more, she realized, this could also help unite and strengthen SONG’s chapters as they scouted for local Free From Fear campaigns.

Kate added: “The folks in Richmond were working to prevent the expansion of a jail, Durham was doing a whole bunch of other organizing, we were organizing in Atlanta, we were doing organizing in Birmingham, but it was all under the broader umbrella of criminalization of black queer and LGBTQ people. Everybody was picking different issues, which makes sense, but it meant that it was [tough] for us as campaign newbies, in some sense, trying to support all of these chapters, they all had different targets, they all had different demands.

“We started to think, what would it look like with [Mary’s] broader vision to test a shared demand, or a shared issue across the region, so that we could help people feel less isolated and more connected? We could leverage our power and we could leverage our lessons versus being like, everybody’s going after a different city manager versus council versus mayor versus judge.”

They consulted their members across the region in late 2016, “and I don’t believe there was one person who didn’t say that they themselves as somebody that they knew hadn’t been impacted by this,” said Mary. At the same time, the group’s leadership was trying to anticipate how their conditions might shift under a Trump presidency. Their close relationships with the Georgia Latino Alliance for Human Rights (GLAHR) and Mijente informed their assessment that detentions by Immigration and Customs Enforcement would soon become more of a threat.

They were also ready for a recruitment reset. SONG was able to absorb many new members through engagement with the mass uprisings against police violence that took place from the fall of 2014 to the end of 2016. But by the end of that year, Mary had seen how unsustainable the cycle of rapid response had become: “By the time January came, I remember us saying ‘comrades, we cannot continue to move like this. It is unprincipled for us to continue to mobilize brave folk out. We just be downtown. You know, just mad, without a demand, without a demand and a strategy. And so that’s when we brought together our base and began to reflect on some of the things that we were seeing as related to fines and fees. It started too, because it was what was happening in our own lives too. But it’s interesting how, when something is so normalized, you just think that’s the way it is.”

With those big-picture assessments and lived conditions in mind, proposals to focus on shared regional campaign work around specific issues were for the first time vetted SONG’s all-membership meeting in January 2017. “We scrapped it out via debate. We like a good debate. And so we debate it and brought proposals around how we could unify around bail and melting ICE,” said Mary.

They realized the local chapters who hadn’t already been running court watch programs, and didn’t yet have a good power map of the issue, might need more exposure to the problem before they could craft legible local campaigns. Mary had an idea that she shared with other staff: “‘Hey, we should bail out our Black mothers for Mother’s Day.’ That was, I think, the turning point.”

The idea of a shared tactic that could be used to further test the contours of bail as a campaign opportunity and identify potential demands and entry points appealed to them. It would also be an opportunity, as Mary explained, “to foster joy and center a pro-Black and feminist and pro-queer politic, and was going to allow us to learn more about the opportunities to actually fight and win on that issue.”

In Spring 2017 SONG got to work helping chapters prepare, writing a fundraising toolkit, hosting house parties, and learning about how to identify people locked up who needed help posting bail. The first Black Mama’s Bailout freed 64 women in seven cities, engaging 350 SONG members and volunteers who raised over $200,000. As anticipated, it helped SONG’s members and staff identify campaign opportunities, including how to put “divest from this bullshit and invest”, as Mary put It, into practice: “We could literally say coming out of bail, how many people needed beds in terms of to be able to get mental health or drugs treatment, how much housing people needed. It was clear where the gaps were.”

It also forced their chapter leaders to identify resource referral agencies, and work in coalition around a shared goal: “Of course, through our lens, are they pro-Black? Are they pro-feminist? Are they pro-immigrant? So calling up shelters to say, ‘do you accept X, Y, Z type of people?’ Getting clergy in the jails to talk to folks to see if they wanna get bailed out, because some didn’t… it helped strengthen our muscles to be in coalition.”

And they made sure to do the work “as our scrappy ridiculous selves,” as Mary said. “We pretty much took over the Fulton County Jail, we had our whole shit out there. It was cute. You know, tables, snacks. We had our banners, you know what I mean? We had music and flowers, we remained true to who we were.

“What was clear and what was spiritually clear was like, Black people, we know we’ve done this before. We’ve bought each other’s freedom before, there is something in that.”

The bailouts tactic spread that year beyond SONG chapters to cities across the country, and along with their engagement with national bail formations co-convened with Movement for Black Lives, Law for Black Lives and Color of Change, set the stage for the formation of the National Bail Out collective, which funneled even more resources to Black-led organizations that hadn’t yet organized around bail, in addition to existing bail funds.

The bailouts (SONG Atlanta held two in 2017) also helped the group visibilize the issue of bail in a local election year, boosting their local campaign efforts. And in November, Councilmember Keisha Lance Bottoms was elected mayor.

“She’d been our nemesis on Council,” said Kate. The group had criticized her along with the rest of the council, who they saw as providing a lack of oversight for local courts and jails. “But she had already forecasted that she was willing to look at bail, I think specifically because of the bailouts and some of the national climate.” Mary agreed: “She had some promises to fulfill, otherwise she would’ve lost [the election].”

Once Bottoms announced her intention to end bail in her first 100 days in office in February 2018, SONG reconnected with the Southern Center of Human Rights, who had been part of the bail outs the previous year, and were helping draft a bill for City Council. But they soon realized they would need to find other attorneys to help craft a strong policy ending bail. “So we hit up Law for Black Lives, our comrades nationally, I’m like, ‘yo, we need our own ordinance… and this is what we think it should include.”

SONG’s members and organizers weren’t consulted by legislators on the draft policy directly, but they packed the council chambers during hearings on the bill, rebutting opponents who testified in favor of continued wealth-based incarceration. Their actions shaped public understanding of the issue, as Kate noted: “We shifted the conversation profoundly in those council meetings, by who we brought and who we held space for, versus it just being the lawyers and then the random people that always talk at every city council meeting for the last forty years.” Just a few weeks into Bottoms’ term as mayor the City Council passed an ordinance banning the cash bail requirement for low-level offenses.

Within a year of the legislation going into effect – and helped by another campaign win, getting Mayor Lance-Bottoms to cancel the jail’s contract with ICE – the daily jail population dropped from an average of 700 to just forty detainees, opening up a new campaign demand in the larger fight to reduce criminalization and incarceration. “[Our partners] Women on the Rise had been saying for years, ‘they need to close that damn jail’. And so once the bail legislation passed and we are all over here, like tired as shit, that’s when the comrades were like, ‘no problem’.”, said Mary. “And then they begin to reassemble and recharge the city with a new demand: It’s time to close the jail, cause it’s empty.” The Atlanta City Council voted to close the Atlanta City Detention Center in April 2019, but the campaign remains ongoing, with a new phase to pressure a different mayor and City Council not to lease the almost-empty jail to a neighboring county.

Lessons for Organizers in Crafting Campaigns

Reflecting on the lessons SONG organizers learned in waging Free From Fear campaigns that seem most applicable to contemporaries today, Mary pointed out that looking for issues around which to wage campaigns can fundamentally change how we see the daily architecture of oppression, like court fees or the imposition of bail: “Particularly with the bond stuff, it’s not as though I haven’t been bailed outta jail before, we get campaign stuff… or like, folks in our families, my survival has been deeply impacted by all of this shit. But once you start seeing it, when it’s not like the crisis normalized thing that you just do, and step into it from a different perspective, it was a game changer and I could just see, it’s eyes wide open on a whole other level.”

Kate also pointed to the impact of designing intersectional campaigns that would change material conditions for many — “not just intersectional like, getting more badges,” as Mary put it. She says the kind of relationship-building required of their members went beyond traditional community-building: “If you’re building community, you’re not necessarily gonna build a campaign, but if you’re building a campaign you’re definitively gonna build more community and oftentimes when folks just get narrowed in community building outside of a campaign, it doesn’t encourage you to build community across other communities.” Mary added, “You tend to just build with folks who sound like you and talk like you, but in a campaign, cut that issue baby. Everybody can get this work. Everybody can get a piece, and you find yourself being able to rock with other people.”

But most of SONG’s chapters that engaged in bail outs weren’t able to craft local campaigns. As Kate reflected later, “That’s ok, that was one of the realities that we were also contending with. We live in a, a sort of a turn up and mobilization time. Cultural organizing has moments of that, and moments of actions that are visible, that you can wrap your arms around and are beautiful, like the bailouts and tactics like that. But a lot of it is carrying the water to sustain work and people and teams and momentum and vision over time.”

She also noted that learned a lot about how to navigate the “inside game” while staying true to their rebel / organizer roles, centering those most impacted by the campaign issue: “We got outpaced by the individual lawyers, activists and the advocates. And they essentially were like, ‘y’all cute. You do the protest, but we’re gonna write the policy.’ Because they’d already written it and gone back and forth and redlined it with the lawyers. They were like eating dessert and we like brought our appetizer, we were just behind.”

“You wanna respond to the targets in real time, especially when they sometimes intentionally try to accelerate the process to see if you can keep up, but there is that sort of dance around, how do you stay with the process, but also try to slow it down so that actually the people impacted can be part of it.”

“How do you elbow out enough space amongst the suits to be able to have it be meaningful and align with our values. And also not do the other lefty thing, which is like, ‘if it’s not gonna be perfect, we don’t want any of it… there’s truth in the fact that we do have to compromise sometimes.”

One element of how they waged campaigns that made that possible? SONG’s willingness to use creative direct action, which she referred to as their ability to “make it a street fight”: “The most powerful points of these different campaigns and the development of the campaigns was when we were able to do it on our terms and make it a street fight in the street versus going in with the suits and being like, ‘am I the only person not wearing panty hose?’

“The reason why we make the street fight is, one, it makes it public. They want to hide in these buildings where nobody can find them and make the policies that ruin so many of our people’s lives. And, two, it evens the terrain. And it also gives us like with the bailouts or with the failure to appear an opportunity to use humor, and to ‘show, not tell’ our vision.”

And another part of the campaign organizing sauce? A willingness to try, test, take risks, before understanding all of the contours of the issue or the power map to their demands. “Whatever beautiful ideas we have, however weird they are. If people wanna try to make them happen in terms of their tactics and action, just do it, you’re gonna spark a sense of possibility in somebody, whether you know them or not, whether they tell you or not, that is the beauty of organizing.”

“Pick something and try it. Doesn’t have to be the perfect issue. It shouldn’t just be one thing that you and your one friend think is important, you do need to explore and build. With our rising political fundamentalism, we also have a rising sense of hesitancy and perfection.”

But Mary pointed out another element of their success in tension with their willingness to try-and-test: their ability to stop responding to a new political moment, and focus on moving the campaign forward: “In 2016, we were just, rapid response, rapid response… but don’t lose the campaign, just cuz the shit popping off, but give people a long term fight that they can engage in. [Ask yourself] what is it about the campaign you’re moving that resonates or connects to what folks are upset about in this uprising moment, and see if it’s an opportunity to move people into that instead of just dropping it and letting it go to the side.”